Stomach.

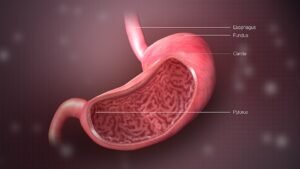

The stomach is a J-shaped muscular bag of about 25 cm in length and weighing about 4 ounces. The inner wall of the

stomach has folds called rugae. The primary function is the storage, but the main function is the brake down the food. Their walls are muscular and strong for food mixing in gestric juice and convert into a liquid called the chyme. The stomach releases the hydrochloric acid, digestive enzymes, and mucus for protein digestion. The Stomach also controls the amount of chyme. Anatomically, the stomach is divided into four regions. It has two openings named.

- CARDIA (esophagus enters the stomach)

- PYLORUS (stomach enters the duodenum)

- Fundus (dome-shaped

- Body

- Greater curvature

- Lesser curvature

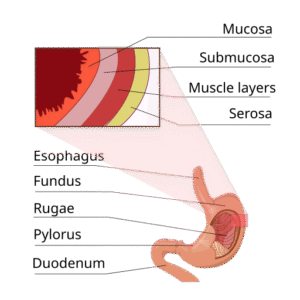

The walls of the stomach are made of four layers:

1. Mucosa.

The stomach mucosa is the innermost, most important stomach wall layer; the continuation of digestive function and serves as the boundary line between ingested food material and the harsh gastric environment. It serves the dual function of digestion and defense, making it extremely important for successful gastric function. Within the mucosa are the gastric pits that end with gastric glands. G – cells also secrete the hormone gastrin, which promotes gastric secretion of the stomach. The layer of lamina propria is connective tissue beneath the epithelial surface, which contains blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and immune defense to provide nourishment and defense. Lastly, there is a thin layer of smooth muscle, the muscularis mucosae, that completes the composition of the mucosa.

2. Submucosa.

The stomach’s submucosa serves as the supportive layer of connective tissue, lying directly beneath the mucosa and above the muscularis externa, and plays an important role in maintaining the stomach wall’s structure and function. Given that the mucosa is responsible for secretion and absorption, the submucosa is offered primarily as a constructed, strong, elastic cushion with nourishment, flexibility, and communication between the layers. The submucosa is consistent with a composition of dense, irregular connective tissue, abundant in collagen and elastic fibers that allow for the stomach to greatly expand after ingesting food and return back to normal after digestion. Additionally, the submucosa contains a vast array of blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerves to facilitate support for the overlying mucosa. The blood vessels supply oxygen and nutrients to the gastric tissues and facilitate the removal of absorbed substances from the lamina propria, the functional area responsible for secretory and absorption functions of the gastric mucosa. Meanwhile, lymphatics maintain homeostasis and fluid balance while providing immune defense. Probably one of the most vital aspects of the submucosa is the submucosal plexus (Meissner’s plexus), containing an array of nerve fibers, part of the enteric nervous system, that regulates local blood flow and coordinates glandular secretions from the mucosa for important phases of digestion or targeted acid-base secretions.

3. Muscular layer.

The stomach’s muscular layer, or muscularis externa, is a unique and highly specialized structure that is involved in the muscular component of digestion. The gastrointestinal tract’s other components typically have only two muscle layers. But the stomach has three layers: longitudinal layers, circular layers, and oblique layers. The oblique layer also allows the stomach to be stronger and more flexible in terms of its storage capacity, churning, mixing, and breaking down food more efficiently.

4. Serous layer.

The serosa outer layer of the stomach wall, forms a smooth protective covering, helping to anchor the stomach within the abdominal cavity while also reducing friction with surrounding organs. It optimizes the stomach’s shape and position while providing a surface and barrier for infection and injury. Additionally, blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerves run through the connective tissue of the serosa and supply nourishment and communicate with the deeper layers of the stomach wall. The serosa is also clinically relevant; diseases, as an example, peritonitis (inflammation of the peritoneum) may involve the peritoneal layer and cause extreme inter-abdominal pain and systemic disease.

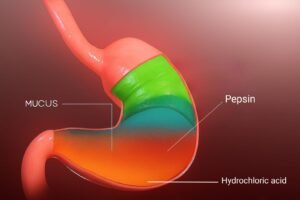

Secrecion of Stomach.

- Mucus

- Pepsin

- Hydrochloric acid

Intrinsic factor (a very important chemical required for the absorption of vitamin B12 in the

intestine)

Function of the Stomach.

- The stomach temporarily stores the food we eat.

- After food enters the stomach, it rests for a short period of time.

- Later on, strong shaking movements, called churning movements, start with both cardia and pylorus openings tightly closed.

- After going through vigorous movements and shaking, the undigested food is now a mixture of acid and other gastric secretions and adapts the shape of a semi-liquid paste.

- This semi-liquid food is called chime/chime, and at this stage, it is ready for chemical

digestion to be carried out in the sm - Hydrochloric acid in the stomach is secreted through the mucus sac and kills bacteria. Or viruses accidentally enter along with food.

- The gestric enzymes lipase, amylase, and pepsin help break down proteins and lipids. (Chemical Digestion).

- Proteins are converted into peptones, and fat is converted into a digestible form.

- The stomach releases the casein, which converts the milk into curd.

- The mucus of the stomach protects the lining of the stomach from burning with the acid.

- The stomach also carries out specific absorptions, like medicines (i.e., aspirin), water, and alcoho, whichl can be absorbed through the stomach. all intestines.

- When chyme is ready and prepared for chemical digestion, the pyloric sphincter opens at short intervals, and the chyme leaves the stomach in a very small quantity by passing through the pylorus.

Pylorus opens into the first part of the small intestine, known as the duodenum.