Definition.

Biological development is the process by which living organisms grow and develop from a single cell into an organism. It includes all the physiological changes that occur during life.

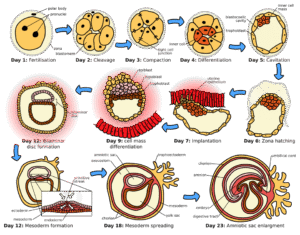

The biological process of development begins at fertilization, when a zygote is present and quickly begins to divide to produce new cells. Following that, these newly formed developing cells undergo growth and changes associated with differentiation and morphogenesis. Morphogenesis is the process by which body plans are constructed or organs and systems are organized within an organism.

Biological development is determined and influenced by genetic and environmental influences at various levels of biological organization. In addition, when maturation occurs within an organism, biological development persists in the form of aging as involuntary structural and functional changes occur over time.

Major Stages of Development.

Fertilization

- Fusion of sperm (male gamete) and egg (female gamete).

- Restores the full diploid chromosome number (46 in humans).

- Produces the zygote (the first single cell of the new organism).

- It detects genetic identity (except in identical twins).

Cleavage

- Rapid series of mitotic divisions without growth.

- Produces many smaller cells called blastomeres.

- Results in a morula (solid ball of cells).

- Purpose: to increase cell number quickly and prepare for tissue formation.

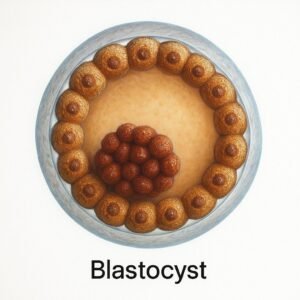

Blastulation

- Cells rearrange to form a blastula:

- Hollow structure filled with fluid (blastocoel).

- Outer cells = trophoblast (help form placenta in mammals).

- Inner cell mass = embryo proper

Gastrulation

- One of the most important stages.

- The blastula reorganizes into a gastrula with three germ layers:

- Ectoderm forms skin, hair, nails, and the nervous system.

- Mesoderm forms muscles, bones, the heart, the kidneys, and blood.

- Endoderm forms the digestive tract, lungs, liver, and pancreas.

- Establishes the body plan (axes: head to tail, left to right, dorsal to ventral).

Organogenesis

- Formation of body tissues and organs from germ layers. These layers form by different mechanisms.

- Each germ layer provides a specific set of organs and other structures, and organizes the first aspects of functional anatomy, as organs are biologically prepared to hold their place.

- Examples:

- The ectoderm forms the future nervous system, skin, and sensory organs. The mesoderm gives rise to muscular structures, bones, blood vessels, and the heart. Finally, the endoderm establishes the digestive tract, lungs, liver, and other structures that develop clearly as internal organs. During organogenesis, groups of cells are precisely moved, differentiated, and organized in such a way that groups of cells produce “tissues” that will ultimately function together as organs.

- Other body organ systems develop like the circulatory, nervous, and digestive systems.

Growth & Differentiation

- Growth: increase in size by cell division & cell enlargement. Growth is what enlarges body structures so that an organism can become larger and attain maturity. Proper nutrition and hormones are also an essential part of normal growth, as is the genetic constitution of the organism.

- Differentiation, in contrast, aggregates processes through which an unspecialized cell, typically known as a stem cell, can become a specialized cell to carry out a particular function, like a nerve cell, muscle cell, or blood cell. The more specialized structure of the body allows for more complex body functions to be performed more efficiently.

- Both growth and differentiation occur in a highly controlled manner as directed by genetic instructions and intercellular signaling. Their purpose is to ensure that each organ forms correctly and functions cooperatively with all other organs of the body.

Maturation

- Organ body systems become fully functional.

- Organism reaches sexual maturity (capable of reproduction).

Aging (Senescence)

- Structural and functional decline of tissues and organs with age.

- Controlled by genetic, cellular, and environmental factors.

- Leads to decreased ability to repair and regenerate.

- Biological development is not random; it is regulated by a set of molecular, cellular, and genetic mechanisms that guide cells from a single zygote into a complete organism.

Mechanisms of animal development.

1. Genetic Control

Development is mainly controlled by genes.

- Regulatory genes (like Hox genes) determine the body plan and organ placement.

- Transcription factors turn genes on/off at the right time and place.

- Master genes (e.g., Pax6 for eyes, MyoD for muscles) can direct entire developmental pathways.

2. Cell Division (Proliferation)

- Controlled mitosis increases the number of cells.

- Timing and rate of division are regulated by growth factors (FGF, EGF, TGF-β).

- Abnormal regulation can cause developmental defects or cancer.

3. Cell Differentiation

- The process by which unspecialized cells become specialized cells.

- Driven by gene expression patterns and epigenetic modifications (DNA methylation, histone modification).

- Example: stem cells form neurons, muscle cells, or skin cells.

4. Induction & Signaling

- Induction = one group of cells sends signals to direct the fate of nearby cells.

- Signaling molecules involved:

- Morphogens (e.g., Sonic hedgehog, BMP, Wnt).

- These diffuse through tissues create gradients and tell cells their “position” and fate.

- Example: notochord releases Sonic hedgehog and induces neural tube formation.

5. Morphogenesis (Shape Formation)

- Processes that shape tissues and organs:

- Cell adhesion molecules (CAMs): help cells stick in the right place.

- Cytoskeleton changes: allow movement, folding, and elongation.

- Apoptosis (programmed cell death): sculpts structures (e.g., fingers separated).

6. Pattern Formation

- Mechanism by which cells “know” where they are in the body.

- Controlled by Hox genes: specify regions along the body axis (head-to-tail).

- Example: mutations in Hox genes can lead to misplaced limbs or extra body parts.

7. Epigenetic Regulation

- Development is not only genetic but also epigenetic.

- Environmental factors (nutrition, stress, chemicals) can influence gene expression.

- Example: maternal diet affects fetal growth by altering DNA methylation.

8. Regeneration & Repair

- Some organisms (e.g., salamanders) use developmental pathways in adulthood for regeneration.

- Humans retain limited regenerative capacity (liver regeneration, wound healing).